I was particularly interested last week by the comments from one of two U.S. economists I really like. These two economists are Jason Furman, who has emerged as a top figure on the Democratic side, and Kevin Hassett, a leading figure on the Republican side. When I have seen them both debate in person, Kevin Hassett usually seems to be enjoying the event more than Jason Furman. Maybe Hassett just has a sunnier temperament.

Kevin Hassett, served as Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers to the President Trump in his first Administration. In Trump's current administration, Hassett holds the position of Director of the National Economic Council. The National Economic Council is responsible for coordinating all major economic policy actions across the top departments. This is a significant role, far beyond just offering advice.

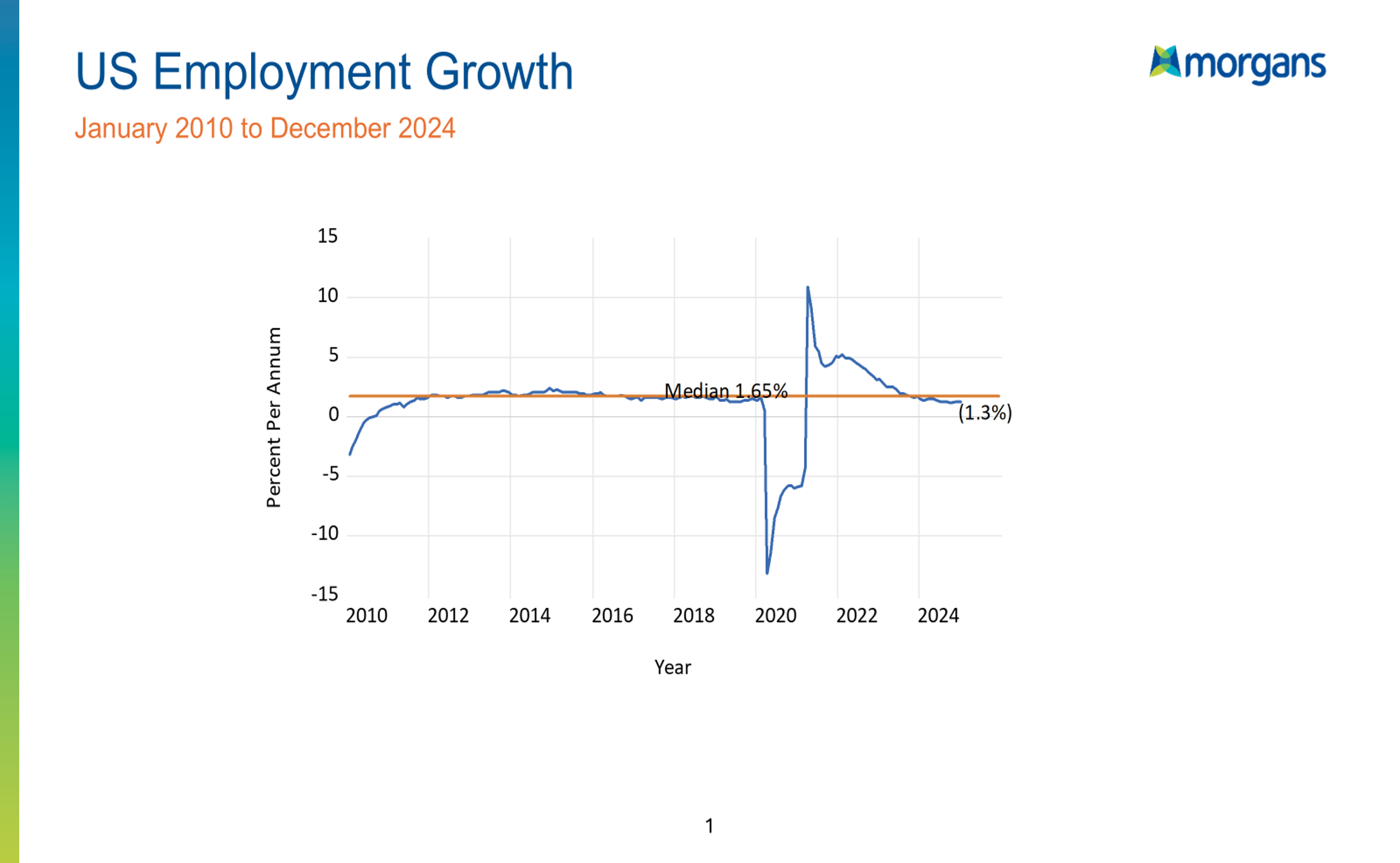

Hassett was discussing the strange movement in the U.S. payroll numbers published by the U.S. Department of Labor. Last week, the numbers came in one million lower than expected. In fact, it wasn't just one million lower for that month; it was one million lower for the previous four years. It appears that during the Biden administration, the U.S. Department of Labor had overestimated payroll numbers by a million workers per month for the entire period, and immediately after the Biden administration left office, those numbers were reduced by a million. I thought this was a particularly insightful observation, as it led me to update all my numbers for U.S. employment.

I decided to examine U.S. employment growth and its median and then compare it with Australia's figures. The data revealed that the median growth rate of employment in the U.S. is significantly lower than in Australia. The median growth rate of employment in the U.S. is specifically 1.65% per year. Including the most recent updates, the current year-on-year growth rate is now only 1.3%. In this case the Fed might cut monetary policy. Employment growth is an easy way to look at monetary policy, though it’s not my preferred model, which is based on unemployment, excess resources in the economy, and current inflation, as well as inflation expectations.

What these models show, both in the case of the Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)—is that the decision-making of central banks is not so much about where inflation is currently, but where they expect inflation to be in the future. This expectation is heavily influenced by the level of unemployment and, to some extent, expectations around that. However, in Australia, as I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, the problem is that unemployment isn't high enough to bring inflation to a low enough level to allow the RBA to reduce rates.

When we look at the U.S. case, employment growth is lower than the long-term median. In this case the Federal Reserve could consider cutting rates. My model, which explains 89.3% of the monthly variation in the federal funds rate since 1982, suggests that the equilibrium Fed Funds rate is 3.9%. This is lower than the current Federal Funds rate of 4.35%. This indicates that the Fed could cut rates anytime it wants to. However, what Jay Powell, the Chair of the Federal Reserve, said at the last meeting was that he thought monetary policy was in a satisfactory position for now. Still, our model suggests that a rate cut could happen soon, as future inflation is expected to be lower than current inflation.

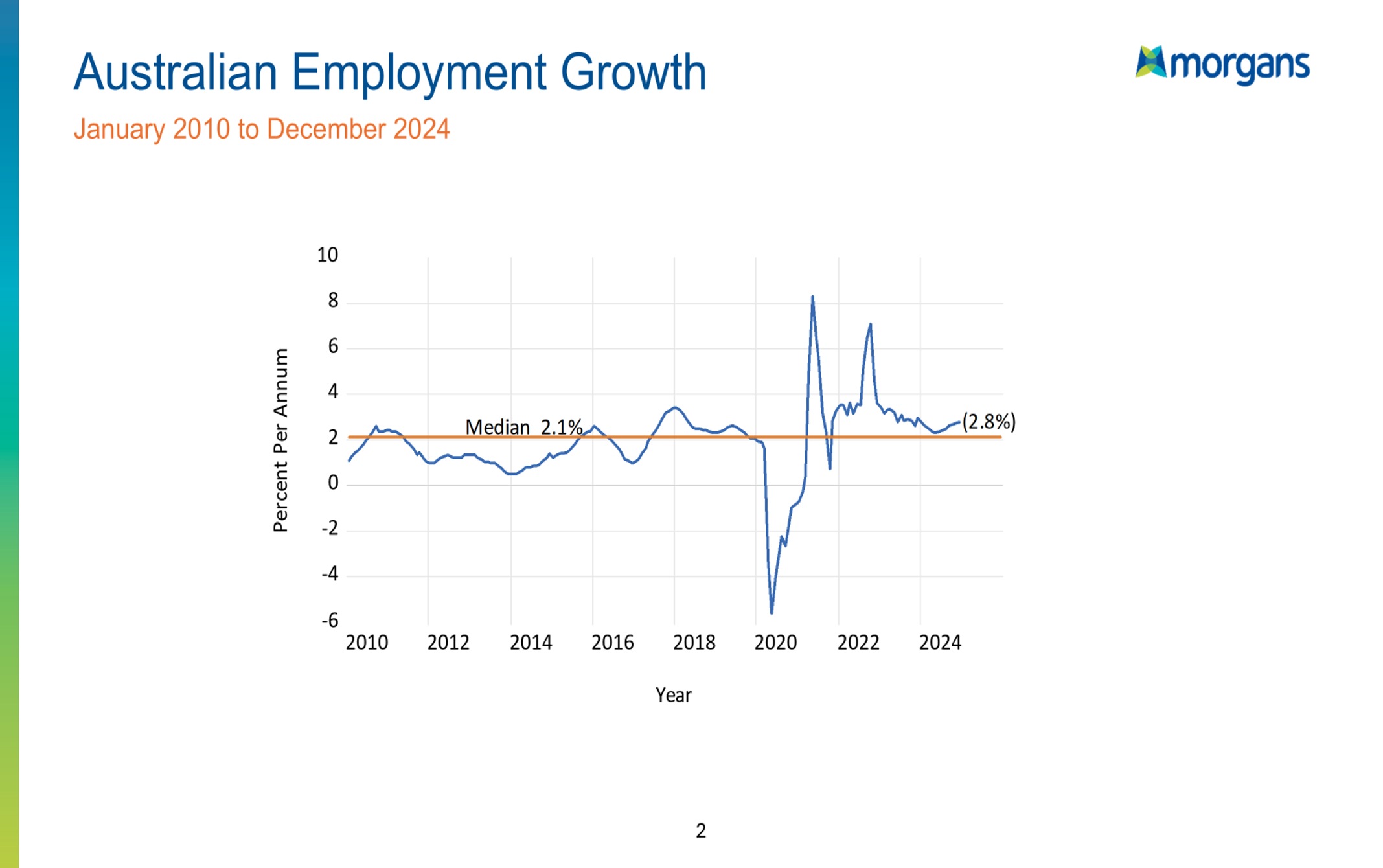

The situation in Australia is different. The median employment growth rate in Australia is higher than in the U.S. The median in Australia stands at 2.1%. This is higher than the U.S. rate of 1.65%. Right now, Australia's rate of employment growth at 2.8% is higher than its long-term median. This is not the usual circumstance in which the RBA could be expected to cut rates. The reason for this is that employment is growing fast is due to the Government adding more workers to the public sector, particularly in the National Disability Scheme.

When we run our model for Australia, it explains 89.4% of the monthly variation of the cash rate since 1992. This is when the Australian cash rate first came into existence. The model suggests that the equilibrium rate is 4.41%, which is slightly above the current Australian cash rate of 4.35%. Based on where future inflation is expected to go, and considering the current level of unemployment, it is highly unlikely that the RBA will cut rates in the near future.

I know that this view doesn't align with the consensus, but I'm comfortable with that, as I often do better when I’m not in line with the majority opinion. The problem is that, as I shared a couple of weeks ago, historical data on the relationship between unemployment and inflation in Australia shows that over the past decade, unemployment needs to reach 4.6% or higher for inflation to be sustained at a level of 2.5%. Australian headline Inflation is falling, and Treasurer Jim Chalmers has been influencing that, as we know from the subsidies on electricity.

However, the RBA's decision will be based on where it expects future inflation to be, and my expectation is that we won't reach the 2.5% target for some time. Consequently, the RBA is unlikely to cut rates at its next meeting.

Morgans clients receive access to detailed market analysis and insights, provided by our award-winning research team. Begin your journey with Morgans today to view the exclusive coverage.