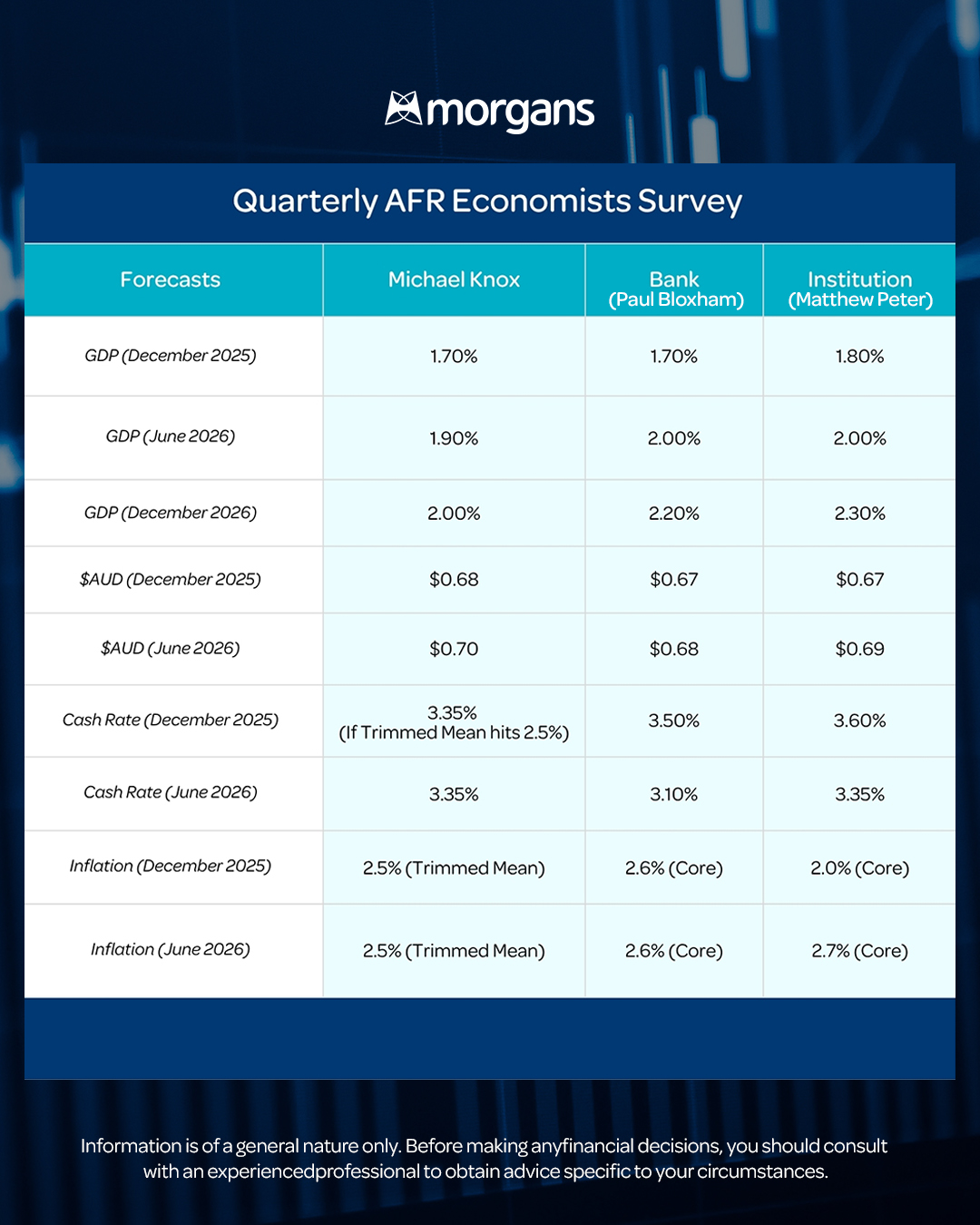

Each quarter, the Australian Financial Review conducts a comprehensive survey involving 39 economists who provide forecasts on key indicators such as GDP, the Australian dollar, the cash rate, and core inflation. Over the past two years, the AFR has also ranked these economists based on the statistical accuracy of their predictions. I have been fortunate to be included in the top ten for both years.

In this article, I will share my own views on the economic outlook, as published in the AFR survey, alongside insights from two other top-ten contributors. One represents a major bank and the other a leading financial institution.

Starting with GDP, my forecast for 2025 is 1.7 percent growth. This matches the major bank’s projection. The financial institution is slightly more optimistic, forecasting 1.8 percent. These figures suggest a broadly consistent view of modest growth.

By mid-2026, growth is expected to pick up. I am slightly more conservative than the others, forecasting 1.9 percent for the year to June. For the year to December 2026, I anticipate growth of 2 percent, while the bank and institution forecast 2.2 and 2.3 percent respectively.

This divergence in growth estimates likely reflects differing views on productivity. In the first quarter of this year, most GDP growth came from the public sector, resulting in very low productivity growth of just 0.30 percent. As growth shifts toward the private sector, productivity should improve. However, I expect less private-sector-driven growth, which informs my more cautious forecast. I also anticipate that employment growth will be driven more by Federal government spending and public sector hiring.

Turning to the Australian dollar, I hold a more optimistic view than the other two contributors. I forecast the dollar to reach 68 US cents by the end of this year and 70 US cents by mid-next year. The major bank expects 67 US cents and then 68 US cents, while the institution forecasts 67 US cents and 69 US cents. My outlook on the Australian dollar is based on the belief that Australia’s rate cuts are nearing completion, while the United States is just beginning its rate-cut cycle.

I have previously stated that the Federal Reserve funds rate could fall to 3.35 percent, assuming it stops at neutral. However, if the U.S. economy weakens, which is likely in a midterm election year, the Fed may cut rates more aggressively. Additionally, the inflationary impact of tariffs is expected to fade next year, leading to a significant drop in U.S. inflation by mid-2026. This could prompt the Fed to cut rates below neutral, weakening the U.S. dollar and strengthening the Australian dollar.

Six months ago, I was asked whether it was worth hedging the Australian dollar. At the time, I said no, as I expected more rate cuts in Australia than in the U.S. Now, with Australia’s rate cuts coming to an end and the U.S. just beginning, it is an opportune time to consider hedging the Australian dollar against the U.S. dollar.

Regarding the cash rate, I expect trimmed mean inflation to fall to 2.5 percent in the ABS estimate for the CPI released on 29 October. If this occurs, the Reserve Bank of Australia could cut the cash rate once more to 3.35 percent by year-end. If inflation does not fall, rates are likely to remain unchanged.

Interestingly, the major bank expects rates to fall not only in December but again by June next year. The financial institution sees no cut this year but expects rates to fall to 3.35 percent by mid-next year. Again, Australia is nearing the end of its rate-cut cycle, while the U.S. is just beginning its own rate cut cycle.

On inflation, I believe the RBA can only cut rates if quarterly inflation falls to 2.5 percent. I forecast this inflation number by December and again by mid-next year. The major bank expects core inflation to be 2.6 percent in both periods, which I believe is too high to justify rate cuts. The institution forecasts 2.9 percent inflation by year-end and 2.7 percent by mid-next year, which also seems inconsistent with a rate-cut scenario. These differences highlight varying interpretations of inflation data.

I have previously noted that the RBA places greater emphasis on the quarterly trimmed mean than the monthly CPI. Governor Michelle Bullock confirmed this in her recent media briefing, stating that while the RBA is transitioning to monthly CPI, it will continue to request quarterly trimmed mean data. This is because the quarterly measure provides a more accurate reflection of services inflation. While monthly CPI may be published, the quarterly trimmed mean will remain central to the RBA’s decisions on the cash rate.